This essay was originally written for Amanda Douberly’s Curatorial Practices Graduate Seminar in the Spring of 2024 at the University of Connecticut.

When my professor informed us that our final project could take any kind of shape or form and was entirely up to us to design, I decided I would take my essay to my newfound skills in InDesign and create a pamphlet style hand sewn book to display the contents of my research and reflections in.

The essay consists of a few styles of the various collecting I participate in. Like many artists, I am prone to holding onto “things,” tokens or souvenirs of my time on Earth. The bits and bobs I find most fascinating. The vignettes detailed in this essay are brief musings and ideas and not at all exhaustive.

I have copied the essay to fit within the confines of a Substack post, but I have included the spreads from the original pamphlet at the end of this newsletter if you would prefer to read it in that form. If you are interested in acquiring a physical hand sewn copy, send me an email. I would love for you to have it.

Without further ado, my rambling thoughts on collecting.

In an effort to understand my own collecting practice, I turned to the internet for answers. Specifically, a “What kind of a collector are you?” online quiz. Peggy.com asked me fifteen multiple choice questions about how I approach art in a gallery, where I learn about art from, tested my art history movement knowledge, tugged at my anxiety of how I don’t like to part with my belongings, and asked me to pick between two types of artists – I decided on Felix Gonzalez-Torres and Agnes Martin over Ian Davenport and Ding Yi, respectively. After reluctantly offering them my email, Peggy declared me a “Spiritualist” and included a triple Venn diagram to describe my collecting practice depicted below:

Peggy describes the Spiritualist collector as someone who is very in touch with their collection: “With each piece in your collection carefully considered, you’re confident and comfortable with each artwork and how they play into your values. Although you are well versed in the world of art, you still relish in taking the role of the listener to learn from others and expand your mind. Your collecting approach is meticulous and thoughtful. Rooted in beautiful and purposeful pieces, each artwork represents a story that is unique to you.” 1

I tend to resist the confinement of a definition in an internet quiz, but as I read their description of me, I nodded my head in agreement the way I may when reading a horoscope, understanding the ubiquity of the descriptors and seeing myself in it anyway.

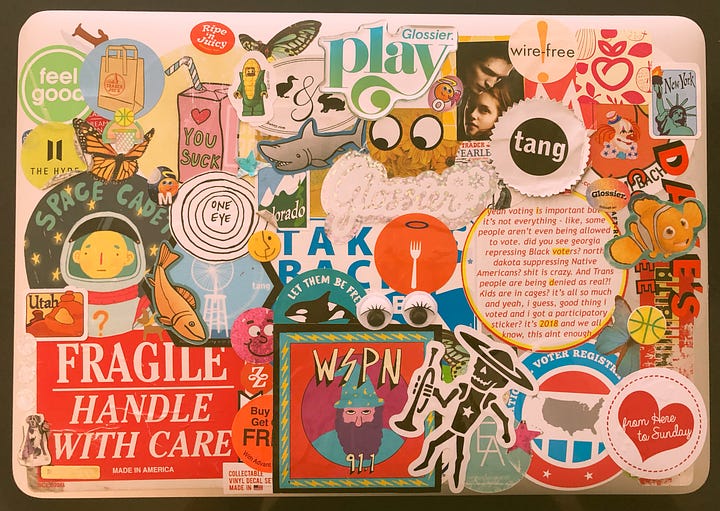

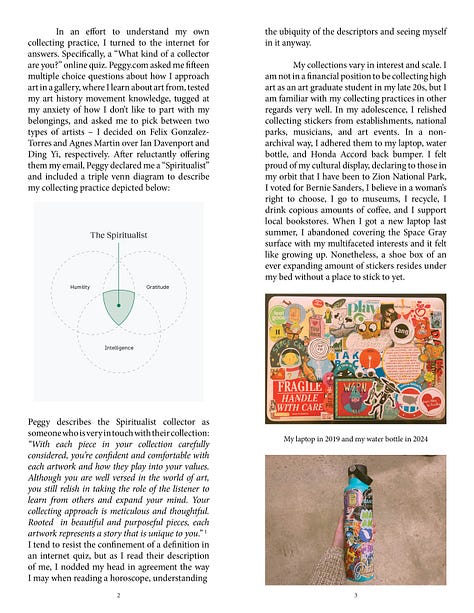

My collections vary in interest and scale. I am not in a financial position to be collecting high art as an art graduate student in my late 20s, but I am familiar with my collecting practices in other regards very well. In my adolescence, I relished collecting stickers from establishments, national parks, musicians, and art events. In a non-archival way, I adhered them to my laptop, water bottle, and Honda Accord back bumper. I felt proud of my cultural display, declaring to those in my orbit that I have been to Zion National Park, I voted for Bernie Sanders, I believe in a woman’s right to choose, I go to museums, I recycle, I drink copious amounts of coffee, and I support local bookstores. When I got a new laptop last summer, I abandoned covering the Space Gray surface with my multifaceted interests and it felt like growing up. Nonetheless, a shoe box of an ever expanding amount of stickers resides under my bed without a place to stick to yet.

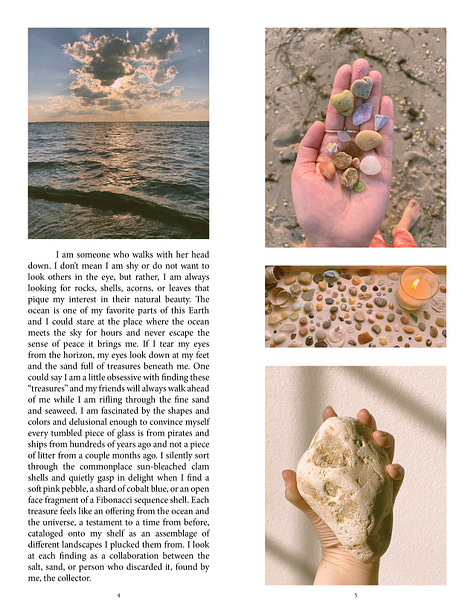

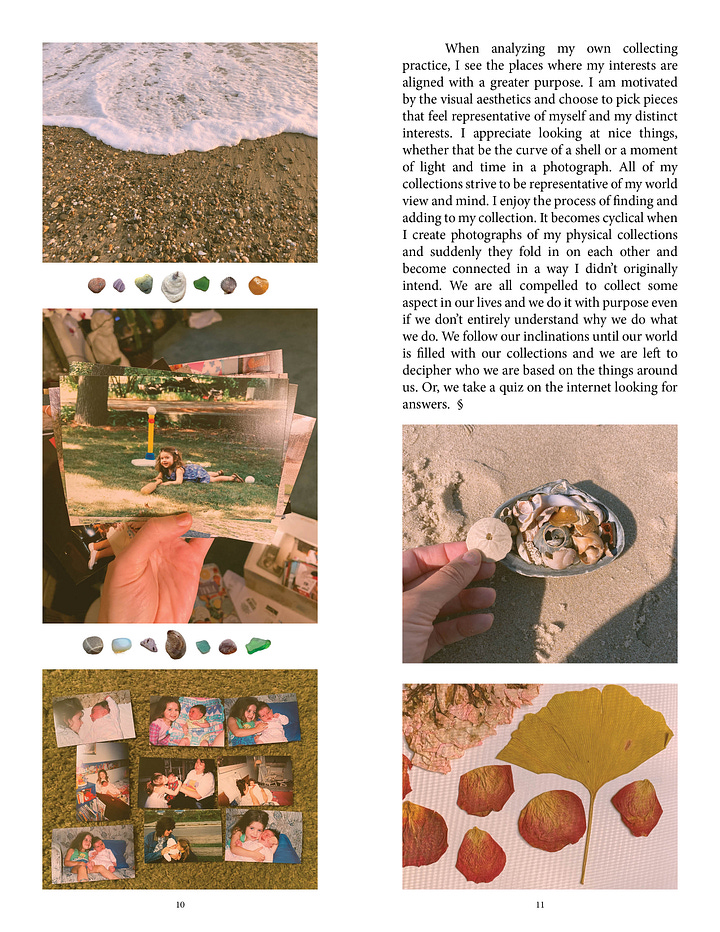

I am someone who walks with her head down. I don’t mean I am shy or do not want to look others in the eye, but rather, I am always looking for rocks, shells, acorns, or leaves that pique my interest in their natural beauty. The ocean is one of my favorite parts of this Earth and I could stare at the place where the ocean meets the sky for hours and never escape the sense of peace it brings me. If I tear my eyes from the horizon, my eyes look down at my feet and the sand full of treasures beneath me. One could say I am a little obsessive with finding these “treasures” and my friends will always walk ahead of me while I am rifling through the fine sand and seaweed. I am fascinated by the shapes and colors and delusional enough to convince myself every tumbled piece of glass is from pirates and ships from hundreds of years ago and not a piece of litter from a couple months ago. I silently sort through the commonplace sun-bleached clam shells and quietly gasp in delight when I find a soft pink pebble, a shard of cobalt blue, or an open face fragment of a Fibonacci sequence shell. Each treasure feels like an offering from the ocean and the universe, a testament to a time from before, cataloged onto my shelf as an assemblage of different landscapes I plucked them from. I look at each finding as a collaboration between the salt, sand, or person who discarded it, found by me, the collector.

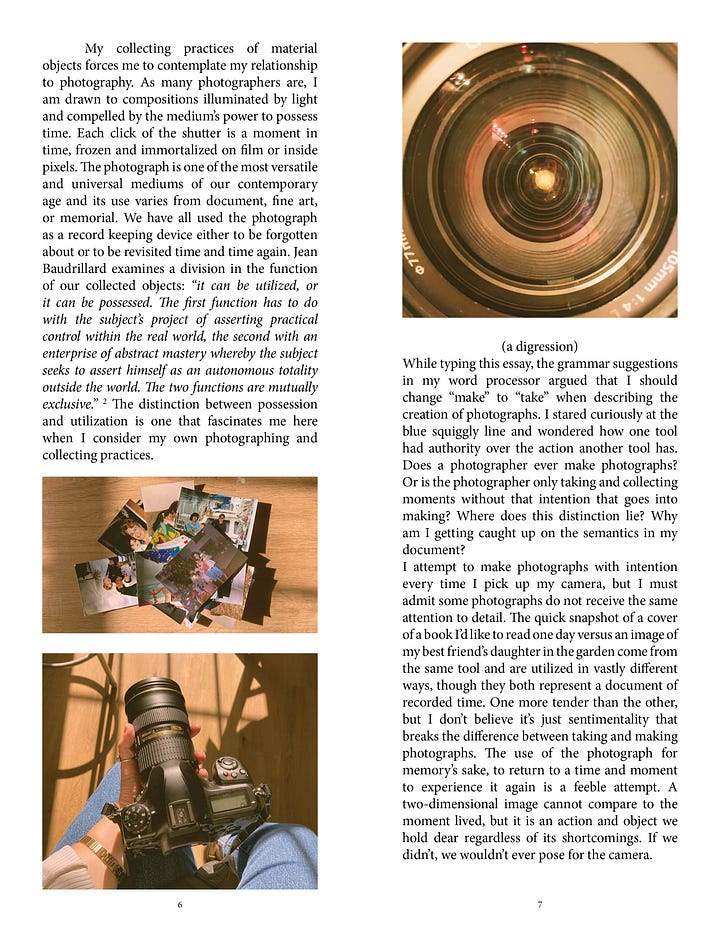

My collecting practices of material objects forces me to contemplate my relationship to photography. As many photographers are, I am drawn to compositions illuminated by light and compelled by the medium’s power to possess time. Each click of the shutter is a moment in time, frozen and immortalized on film or inside pixels. The photograph is one of the most versatile and universal mediums of our contemporary age and its use varies from document, fine art, or memorial. We have all used the photograph as a record keeping device either to be forgotten about or to be revisited time and time again. Jean Baudrillard examines a division in the function of our collected objects: “it can be utilized, or it can be possessed. The first function has to do with the subject’s project of asserting practical control within the real world, the second with an enterprise of abstract mastery whereby the subject seeks to assert himself as an autonomous totality outside the world. The two functions are mutually exclusive.” 2 The distinction between possession and utilization is one that fascinates me here when I consider my own photographing and collecting practices.

(a digression)

While typing this essay, the grammar suggestions in my word processor argued that I should change “make” to “take” when describing the creation of photographs. I stared curiously at the blue squiggly line and wondered how one tool had authority over the action another tool has. Does a photographer ever make photographs? Or is the photographer only taking and collecting moments without that intention that goes into making? Where does this distinction lie? Why am I getting caught up on the semantics in my document?

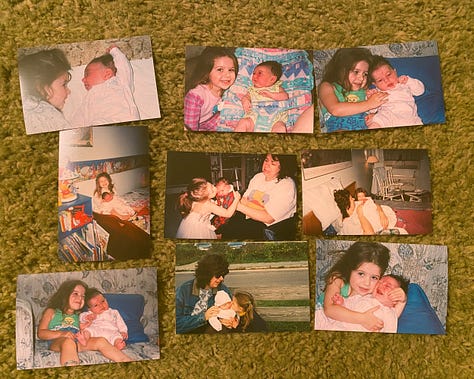

I attempt to make photographs with intention every time I pick up my camera, but I must admit some photographs do not receive the same attention to detail. The quick snapshot of a cover of a book I’d like to read one day versus an image of my best friend’s daughter in the garden come from the same tool and are utilized in vastly different ways, though they both represent a document of recorded time. One more tender than the other, but I don’t believe it’s just sentimentality that breaks the difference between taking and making photographs. The use of the photograph for memory’s sake, to return to a time and moment to experience it again is a feeble attempt. A two-dimensional image cannot compare to the moment lived, but it is an action and object we hold dear regardless of its shortcomings. If we didn’t, we wouldn’t ever pose for the camera.

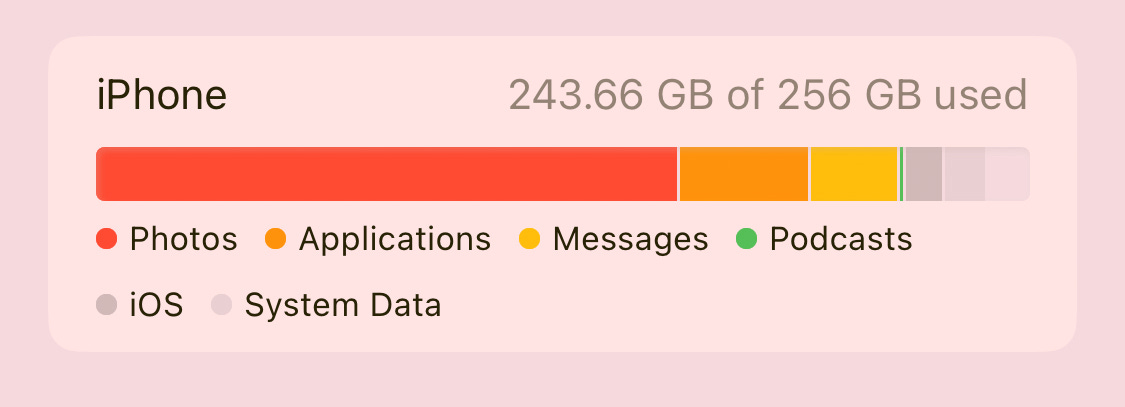

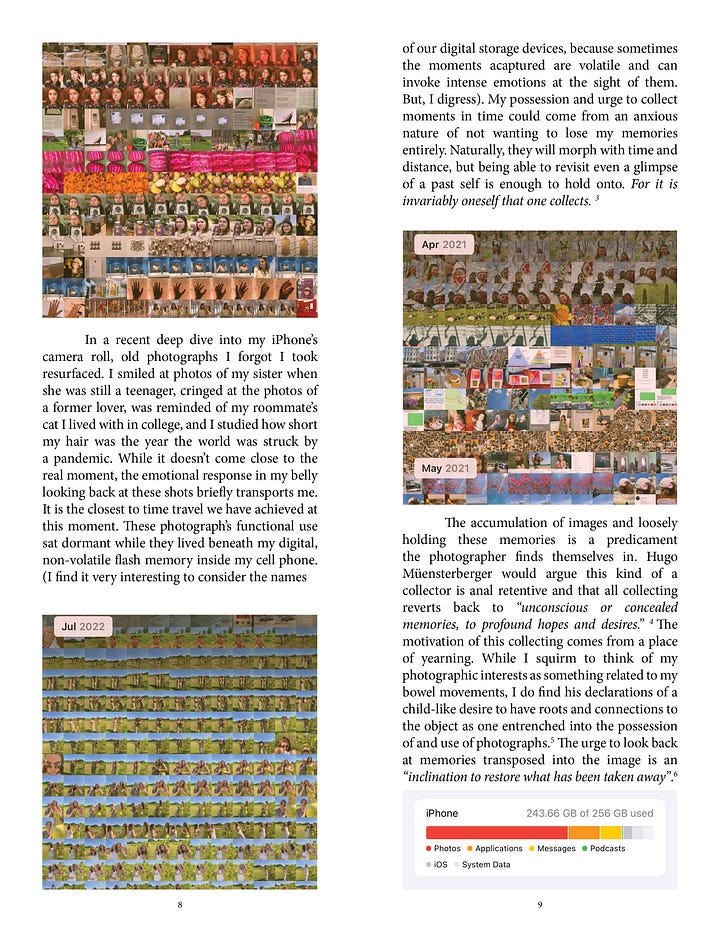

In a recent deep dive into my iPhone’s camera roll, old photographs I forgot I took resurfaced. I smiled at photos of my sister when she was still a teenager, cringed at the photos of a former lover, was reminded of my roommate’s cat I lived with in college, and I studied how short my hair was the year the world was struck by a pandemic. While it doesn’t come close to the real moment, the emotional response in my belly looking back at these shots briefly transports me. It is the closest to time travel we have achieved at this moment. These photograph’s functional use sat dormant while they lived beneath my digital, non-volatile flash memory inside my cell phone. (I find it very interesting to consider the names of our digital storage devices, because sometimes the moments captured are volatile and can invoke intense emotions at the sight of them. But, I digress). My possession and urge to collect moments in time could come from an anxious nature of not wanting to lose my memories entirely. Naturally, they will morph with time and distance, but being able to revisit even a glimpse of a past self is enough to hold onto. For it is invariably oneself that one collects. 3

The accumulation of images and loosely holding these memories is a predicament the photographer finds themselves in. Hugo Müensterberger would argue this kind of a collector is anal retentive and that all collecting reverts back to “unconscious or concealed memories, to profound hopes and desires.” 4 The motivation of this collecting comes from a place of yearning. While I squirm to think of my photographic interests as something related to my bowel movements, I do find his declarations of a child-like desire to have roots and connections to the object as one entrenched into the possession of and use of photographs.5 The urge to look back at memories transposed into the image is an “inclination to restore what has been taken away”.6

When analyzing my own collecting practice, I see the places where my interests are aligned with a greater purpose. I am motivated by the visual aesthetics and choose to pick pieces that feel representative of myself and my distinct interests. I appreciate looking at nice things, whether that be the curve of a shell or a moment of light and time in a photograph. All of my collections strive to be representative of my world view and mind. I enjoy the process of finding and adding to my collection. It becomes cyclical when I create photographs of my physical collections and suddenly they fold in on each other and become connected in a way I didn’t originally intend. We are all compelled to collect some aspect in our lives and we do it with purpose even if we don’t entirely understand why we do what we do. We follow our inclinations until our world is filled with our collections and we are left to decipher who we are based on the things around us. Or, we take a quiz on the internet looking for answers. §

References:

1 Peggy. “The Spiritualist.” Peggy, www.peggy.com/the-spiritualist. Accessed 20 Apr. 2024.

2 Elsner, John, et al. “The System of Collecting.”

The Cultures of Collecting, Reaktion Books, London, 1997, pp. 8.

3 Elsner, John, et al. “The System of Collecting.”

The Cultures of Collecting, Reaktion Books, London, 1997, pp. 12.

4 Müensterberger, Werner. Collecting: An Unruly Passion: Psychological Perspectives. Princeton University Press, 2014, pp.

5 Muensterberger, Werner. Collecting: An Unruly Passion: Psychological Perspectives. Princeton University Press, 2014, pp. 15

6 Muensterberger, Werner. Collecting: An Unruly Passion: Psychological Perspectives. Princeton University Press, 2014, pp. 21-22

To view as pamphlet spreads:

For inquires on physical copies, email me at mshamilton1221@gmail.com or message me here!